Listen to the podcast here:

You can also find our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Podcasts and Spotify.

Written Version:

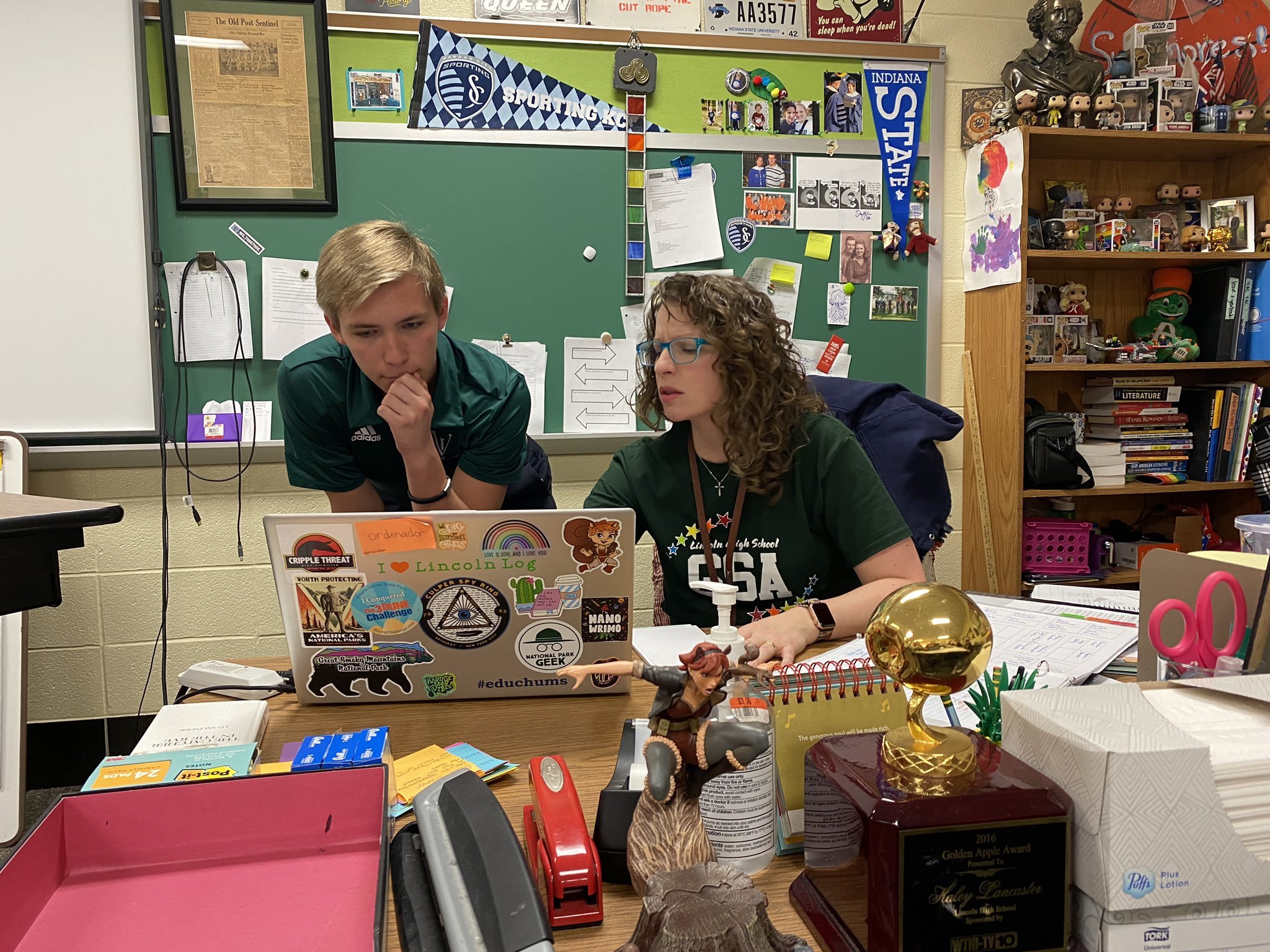

Place-based projects inspire students to engage with their surroundings and assume leadership in their educational explorations. Haley Lancaster, a high school English teacher from Vincennes, Indiana, lives and breathes the history of her place. Hoping to motivate her students to become good stewards of the town, Haley applied for, and was awarded, the 2021 National Signature Project Award. Haley shares how this project exemplifies everything she loves about living and teaching in her rural hometown.

"I have always been a talker. I have always been an entertainer. And so, teaching high school English is the best way I can do all of those things. I can talk. I can entertain. I can teach all day long, and I like the collaborative environment of teaching."

Education, and history, runs deep in Haley’s family, from her aunt to her great, great, great grandfather who helped charter his Indiana county’s public school in 1875. When it came time for Haley to chart her course through life, she too chose education. Haley teaches at her hometown school, Vincennes Lincoln High School. Being at home, she is able to contextualize her life and her work through an intimate knowledge of the place:

"I've been here for 16 years and this is the school that I graduated from. I graduated in 2001 and I was raised here in this town. I spent my whole life here, but my parents always liked to remind me - I love being a Hoosier - they do remind me I was born in Illinois. I'm like, we don't count those nine months that I was there! No shade to Illinois. They're right across the river, so I can yell at them if I wanted to."

While she knew that small towns were dear to her heart, it was one of her own teachers that guided Haley’s career back home:

"While I was student teaching, I got a phone call from someone here in Vincennes. It was like, 'Hey, we heard you're graduating and we need a full-time sub. Would you like to come in and be this full-time sub? It's for Kay Henderson. And - I'm not gonna cry - Kay was my teacher. She's one of my favorite teachers, and she is why, one of the reasons, I became a teacher. She was having some medical issues and needed to take the semester off, so I came down and I was like, 'Subbing or grad school? Let's decide.' So being a full-time sub was an opportunity I couldn’t pass, and Kay ended up retiring, and so I had the opportunity to apply again to stay full time, and then that's what happened. And in the meantime I met a boy, and then lo and behold I ended up marrying him, and here we are. I'm the small town girl still in the small town."

Embracing your rural roots is something Haley values greatly. This is even reflected in her favorite lesson to teach: Shakespeare. Although she admits that the subject “Is such an english teacher cliche,” she shares how students begin to appreciate the work more when they realize it connects to their own experiences:

"Shakespeare himself was a rural kid; wasn't he? Stratford-upon-Avon is not the big city. He's a fish out of water, and he brought his rural experience with him. I think when you look at a play like As You Like It, that's a play written by a kid who knew small town country life, for sure."

Much closer to home, Haley shares too how reading books that take place in Indiana with students begins to weave together lived experiences and local history, blurring the line between classroom and community:

"Teaching setting is one of my favorite things. To get kids to realize that it's more than just the physical place where the story takes place because it's also - it's time, it's place, and it's also social context, and the social context is really, like, where we get into that idea of an identity of a place."

Pursuing this passion for uniting student experiences with place histories, and as a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Haley applied for the National Signature Project Award. The Award, granted by the National Rural Education Association and Rural Schools Collaborative, helps any rural classroom teacher in the United States to lead a place-based project of their design. Haley won with a project to ignite a student-led effort focused on Vincennes’ Revolutionary War-era history:

"Yeah! You can't talk about the American revolution, and you can't talk about Indiana history, without talking about Vincennes; and I'm sure anyone like Illinois, Michigan and that would be in the Northwest Territory gets like a little Jeopardy trivia about Vincennes, because out of this place came five states, because of the capture of Fort Sackville in 1779. By preventing the British from moving farther west, it weakened their overall control and so at the Treaty of Paris then they were able to negotiate out more of this land."

To commemorate this event, and the commander who led the assault, the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park was built in the 1930’s. Haley volunteers at the park, and was inspired to use her school’s Youth Advisory Council to develop the site even more:

"I will say that the the seeds for the group were planted before me. The Youth Advisory Council has been around for about four years, and it was under the leadership of one of the history teachers, and he retired. And when he retired, he told the park rangers, like, 'I think you need to ask Haley, and see if Haley will continue it.' And by then I was already volunteering at the park myself just because I felt like it, and I'm good friends with one of the park rangers, and so it was just a natural fit. Like, 'Yeah, Absolutely I'll do it, that's fantastic!'"

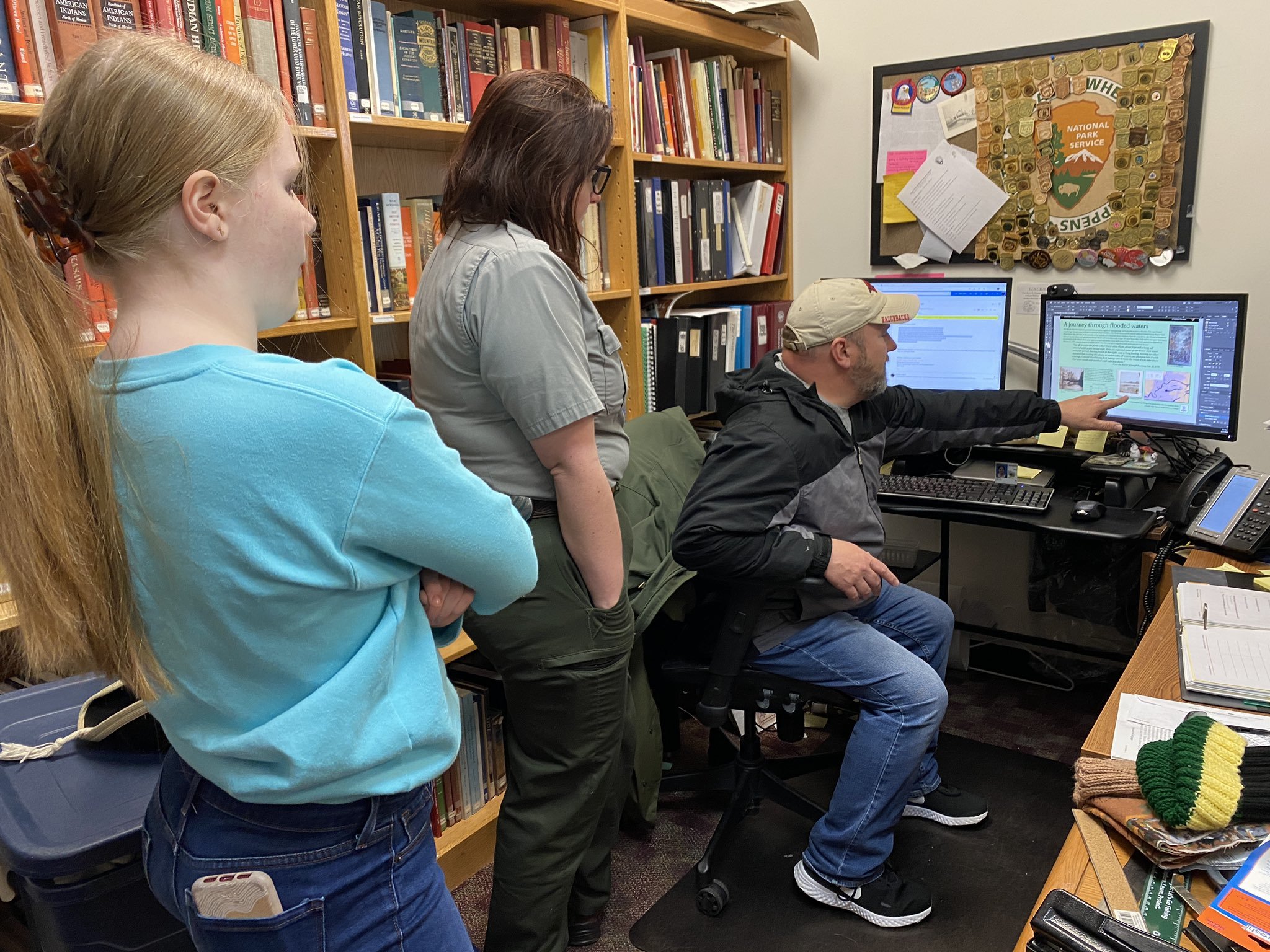

In particular, Haley sought to work with students to install a wayside, a large infographic sign, that utilized the students’ own research to enhance visitors’ experience at the park:

"So our project is that we are designing a wayside for our local national historical park. It is the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park. It is the largest monument of its kind outside of Washington, D.C.; it looks very reminiscent to the Jefferson Memorial in terms of a rotunda with colonnades. And it is on the banks of the Wabash River at the approximate location of where Sackville was located…the park property is the Memorial and large grounds. There's a visitor center, there's a couple of statues, there's a bridge that is now called the Lincoln Memorial Bridge which commemorates Abraham Lincoln crossed over into Illinois from his boyhood home here in southern Indiana, and there are waysides about local history and then the history of the park, the story that they're trying to tell. The idea was for the students to visit the park and understand the whole picture and then pick a wayside that would help fill in the gaps of the story that is being told…and so they decided to focus on something related to the river."

Haley explains that the students chose to focus on the Wabash River, a feature so central to the place and story, but oddly missing from much of the park’s signage:

"We're interested in the idea of flooding because the flooding of the Wabash river is integral to the story of the capture of Fort Sackville. George Rogers Clark decided to march from the Illinois side and capture Fort Sackville from the British in February because he knew that they'd be caught unawares. The British had strong allies with the local Indian Tribes, and most of those Tribes were away for the winter–they were at their regular home hunting grounds. He had a reduced force, obviously it's freezing cold and not a lot of action usually happens in the winter, and basically it was just a way of having the element of surprise. Clark and his men marched for 10 days in freezing cold flooded water. One of the murals inside of the rotunda–if you visit the park and you go in, there are seven murals that tell the story of Clark and the capture of Sackville, and how it advanced westward expansion in the United States–is mural three or four that depicts Harrison and the men trudging through the water. So, we're working together and getting our images now and finalizing the images."

Hoping to capture that history for the project, Haley’s students set about learning more, and crafting ways to share back the information they uncovered:

"I have a girl right now researching some flood water data for the Wabash up until when the levy was put in...I got a kid who did a little bit of graphic design for me for what we think we're going to have on the background, and now we're just at the point where we're trying to piece it together and finalize it, and then the park's going to clean it up for us because...I am dangerous with Adobe InDesign but the the rangers at the park really know what they're doing, and they're excited to do that because they're just excited that the kids are giving their input and putting the design in so we can kind of get the rough draft going for them and then the the park rangers can finish it up for us."

Along with sharing more about the river’s role in the site’s importance, Haley hopes that the wayside will also make the memorial, and the artwork and information it contains, more accessible to community members:

"The other thing that we saw was a gap is that...because it is it was built between 1931 and 1933 before things like ADA existed, disabled visitors cannot get up into the Memorial, and so that allows us to have another image from the inside of the Memorial for visitors to see. There is a wayside on one of the park's grounds that talks about the murals, about Ezra Winter who painted all the murals, and it has one of the images inside, but this gives us another opportunity to feature one one more of those murals for park visitors."

As an integral part of the surrounding area, Haley recognizes that the deeper significance of this project is an overall investment in the local community itself:

"It is very much a place where people spend their time walking the grounds you see people going along the levee walk and the riverwalk. I think everybody in town has like family pictures, senior pictures, baby pictures on the on the banks of the Wabash with the Memorial in the background. I love how it was just such a huge part of our community, but I like to remind kids about the significance of like...this is a national park site, this is just not like this rando big building!"

And most importantly of all, the National Signature Project Award allowed Haley to empower students themselves to take on the task of learning about their place, and working to preserve and share its unique history:

"There's actually not a lot of opportunities that are true community service that you're going out and you're doing something that the community can can, um, benefit from. A lot of kids get involved in things like student council where you're doing canned food drives at school, or you are collecting donations for the pet port at school. That's a valuable good thing to do but a project like this, like, I really wanted to do something that gets kids in the community going to do things."

Reflecting on the subject of community and place, Haley had this piece of advice for early-career rural teachers out there.

"I think that it's one thing they have to consider when you're teaching in a rural community if you take that job it's not just taking the job it's also being part of the community itself it is possible to have that healthy work life balance but acknowledging your par tin being part of the larger picture and I would encourage everybody to learn about your community to to not like it's easy to to be the teacher and go to the basketball game on Friday night or to go to the football game but go visit the local sites go eat at the restaurant go shop at the businesses because that's where your students are and that's where their families are and that's where you'll really learn about what their lives are like and let me tell you nothing makes a kid's day when you ask to sit in their section at a restaurant so we're always talking about building relationships that's one way that you can do it."

Thank you for engaging with this episode of the I Am A Rural Teacher Podcast. We’d like to thank our partners at the University of Indianapolis and the National Rural Education Association for collaborating with us on this episode. Special thanks to Haley and congratulations to her and her students for their work on the National Signature Award Project. The I Am a Rural Teacher campaign is made possible by a grant from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.