Content warning: Holocaust*

Listen to the podcast here:

You can also find our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Podcasts and Spotify.

Written version:

Hello, and welcome to the I Am A Rural Teacher Podcast, a project of Rural Schools Collaborative!

The bonds forged among people in rural places are often driven by how community members can relate to each other, and how they share something in common. However, rural schools can also create a fantastic environment for learning about other cultures in a real, one-on-one way.

Taylor Kilgore and Linda Hooper collaboratively run the renowned Paper Clips Project at Whitwell Middle School in rural Tennessee, which focuses on remembering and learning from the tragedy of the Holocaust. These two outstanding educators share how this project has not only been a classroom lesson for their students, but a medium for deeper understanding and connection between community members.

Both Taylor and Linda love living in rural Whitwell, and Taylor shares how her education journey led her back home.

Taylor: I actually am from here. I grew up in Whitwell, I have always been here, graduated from the high school. And so when I left to go to school - my mom is also a teacher, this is like year 36 for her, so I knew growing up that I wanted to be a teacher as well - I left, went to a small liberal arts school, got my degree in history and geography with my license to teach, taught at the high school out there where I graduated from, Cumberland, a couple of years, and then decided to come back home and i've been home ever since.

Linda also can’t imagine being anywhere else but a rural place, largely because of the ability to get hands-on with school and community projects.

Linda: I believe in, I love living in, rural communities. I believe that everybody should be involved. Nobody - you should never complain about anything that you've not spoken up about ,and that you've not tried to do something about. If you want something done, you go do it, and you find out who's in charge so that it can be done, and you have a plan. You know what it's going to cost, what it's going to benefit. I think that's really important to me. The most important thing about living is being involved wherever you are and whatever you're doing. Get involved!

Both women work on the unique Paper Clips Project, which was started by Linda in 1998 when Taylor herself was a student at the school. The project focuses on expanding students’ knowledge of the Holocaust and Judaism, with the goal of creating more culturally aware citizens, and it continues to this day with Taylor as a lead teacher.

L: Our kids really did not have opportunities to meet or know about other cultures or other races, so I'm sitting there and I'm thinking, 'Well, what are we going to do? How can I help our kids so when they go off to college or get a job or whatever and they meet different kinds of people they know how to interact with them?' So, I went to our parent advisory commission and I laid it out for them. I told them what the study would involve and so on and so forth. Then I went to the ministerial association and I laid it out to them, because these are people who have a powerful influence in your community. And then I went to Sandra Roberts, who was the eighth grade social studies teacher, and I said, ‘I'd like for you to do an after-school study with our kids via the internet, and you aren't going to get paid for it. I'll give you some free time, I'll give you a little what perks I can, but we don't have any money to pay you,’ and she was all interested in that. So the first year, we required parents or some adult in the family to come with the child, and we had about I think 30-40 kids that year after school.

T: Linda and David and Sandy will tell you - those were the three founding teachers and the principal and assistant principal - they'll tell you they didn't know either. And I remember as a group six student, they were still learning with us. We would get in the floor, we would ask a question, and they would say, ‘You know what? I don't know the answer to that. Let me do that with you, let me learn what you're learning

L: And they began to talk about what they were studying and what they were learning, and people began to call and ask questions, and could they come and sit in, and you know we were very open to that. So at the end of that year, so successful, and I had people ask, ‘Well, will you do it again?’ and I said, ‘Yes, but I can't continue to ask Sandra to do this with no pay.’ So it was managed to carve out a time during the day so that all eighth graders could participate.

T: I actually have my Master’s in Holocaust and Genocide Studies, so I start with the ending of World War I, and I bring it all the way up to the beginning of World War II. We are very unique. Our kids do know more about the Holocaust maybe than most adults, even those that have studied the Holocaust. So what we do here is not what you would see in most public schools.

At the start, the project was focused on education and didn’t involve paper clips. Linda and Taylor explain how paper clips became an important aspect of the project and how it has continued to grow over time.

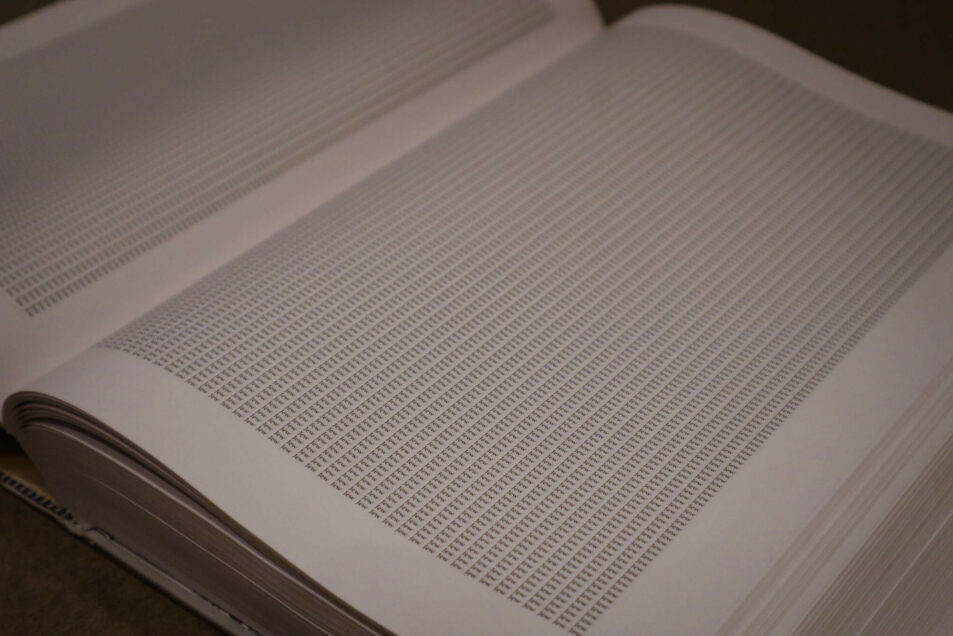

L: One day, one of the students came into my office and she said, ‘Miss Hooper, I just don't get six million.’

T: We talk about six million Jews being murdered by the Nazis…what does 6 million look like? And when you're from a town that only has 1700 people, even a million people, or the million and a half children, is hard to grasp.

L: And she said, ‘Can we collect something, so that we can see?’ And I said, ‘Well, but it has to be meaningful.’ Well, within a week, she came back, and she had a letter prepared. She sat down across from my desk and she said, ‘We're going to collect paper clips.’ And I said, ‘Now, I told you it had to be relevant, not toothpicks or pull tabs.’ She said, ‘Just give me a minute!’ [laughs] And she had learned that Vaaler, who was a Jewish gentleman, is credited with the invention of the paperclip, and that Norwegians wore them on their lapels during World War II to protest Nazi policies. So we started sending out letters…long story short, we were inundated with paper clips! [laughs]

T: The national news gets ahold of it and from there it just kind of exploded. We had paper clips literally pouring in. I remember counting them in my fifth grade class; we would get hundreds a day, so much so that the post office told us that they wouldn't deliver our mail anymore. They had to bring it in like crates, and so we had to go get it physically [laughs] and carry it in. So we had all kinds, and by the time that we stopped counting, we had over the 11 million.

L: We stopped counting them at 30 million.

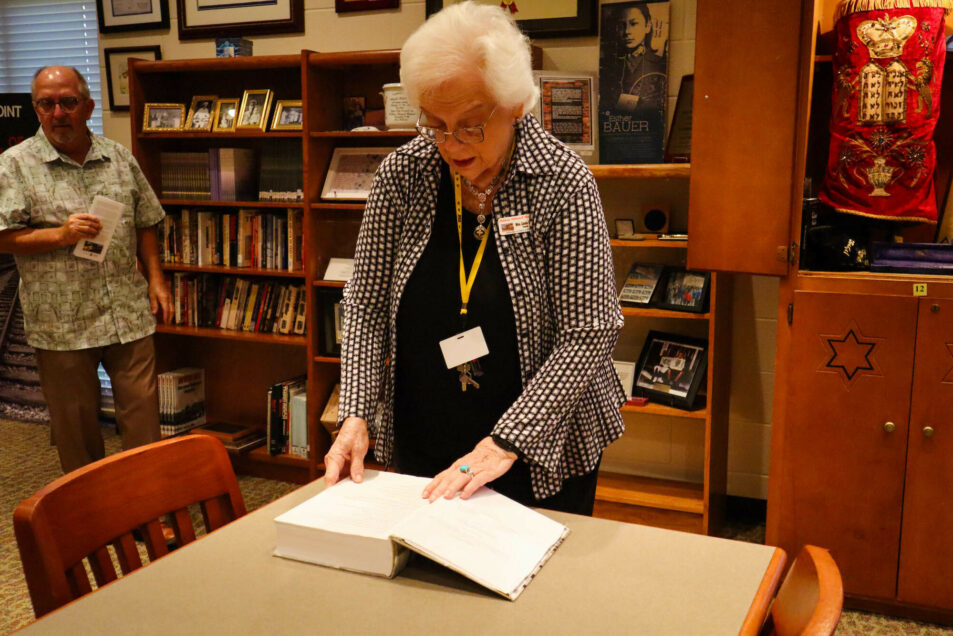

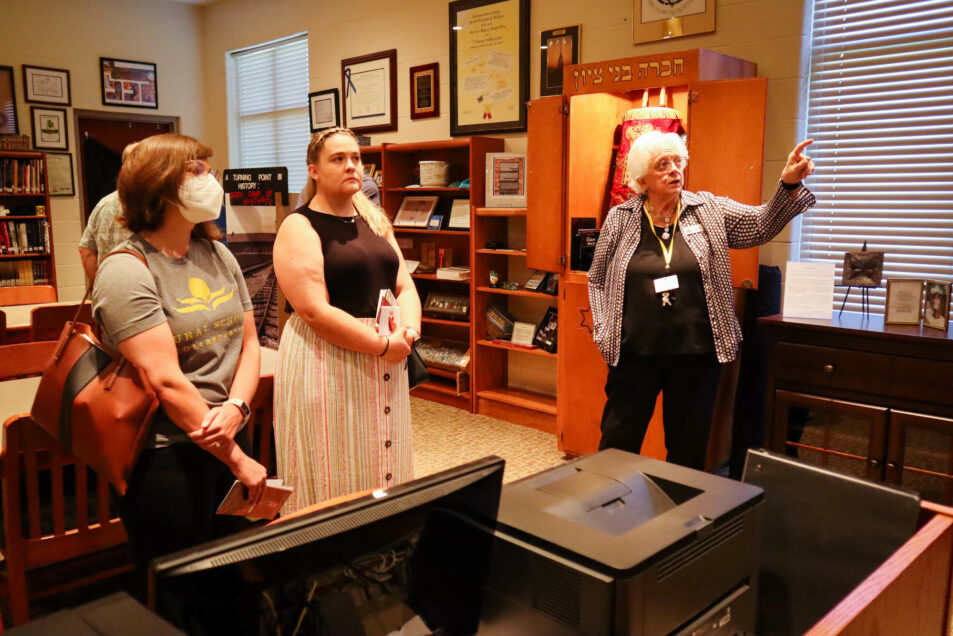

T: [laughs] We stopped counting at 30 million, but we probably have closer to 40. We have 30,000-plus letters because again, stopped counting those, but we get some every day. Now we are sitting in the artifacts library, where all the things that have been donated have come together.

We interviewed Taylor and Linda in the artifacts library at Whitwell Middle School, which contains precious donations of books and Holocaust pieces from around the world. Each woman shared their most treasured artifacts in the collection with us.

T: Actually I have two. This particular Torah was smuggled out of Lithuania. When Hitler started targeting them, somebody knew, ‘We are going to have to preserve this history.’ They smuggled it to South Africa, things in South Africa, eventually in World War II it was not safe either, so it goes to Toronto, Canada, and from Canada it comes to us. it had not been used at all since World War II until a few years ago when we had a Bat Mitzvah here. They actually read from the Torah, and that was the first time it had been used, and I just love that story. The second one is the jacket. In my master's classes, one of the things they always said was, 'We have 11 million documented cases. Hitler killed 11 million people. He took everything down. On that one you can see that he reused the numbers.

L: I really think number 25, the tree. It was created by this gentleman for he and his wife's 50th wedding anniversary, and there are 86 paperclips on there, and each one of them represents a member of their family that was murdered by the Nazis, both he and his wife. And I think about my own family, and I think about 86 people that were murdered just because they opposed a policy.

Another moving experience at the school is climbing aboard a railcar used to transport people to concentration camps. It is accompanied by a monument dedicated to the children killed in the Holocaust.

T: So then we had to decide how we were going to put and display the 11 million, and Linda said a rail car would be fantastic, if there was one, and is there even a rail car from that time period still around? And Peter and Dagmar went and found one. They found one in Germany. Everything was donated for the car to come back across to the United States. It actually was in the port of Baltimore on 9/11, and it left just hours before the first plane hit the Twin Towers. It comes all the way to Chattanooga, they get it on a local trucking company, and they bring it across, and that's how we end up getting it with the project.

L: We have 11 million in an authentic car, we have 11 million in a monument to the children of Terezin. We still have so much interest in this project. People come - a couple weeks ago we had a group from France. You can go to the local grocery and pick up a key to the car, and you can visit the car and it has an audio guide to it, anytime you want.

Considering its primary goal of fostering understanding of other cultures, an enormous success of this project is the network that the school has built outside of the community, connecting their small Appalachian town to the rest of the world.

T: We travel often with our kids. One of my favorite memories is actually when we took a group to Philadelphia. We have a very, very close relationship with a synagogue in Philly. They come here every year, bring a group of eighth graders and their parents, they tour the rail car, they actually go to a church service here, so they can see how we worship. And we go to them every couple of years, and our kids go to a synagogue. and they actually go through a service with our Jewish friends. They get to stay in the houses of our Jewish friends, so they are partnered with somebody, they get to eat the Jewish food and experience their culture literally hands-on. We have had kids go to Israel, and they actually met Livia Bitton-Jackson who wrote I Have Lived a Thousand Years. They came back with all of these stories, where they had seen different things in Israel. And they had met with her, and they had all kinds of conversations about what she was doing in the camps. And you know, once these Holocaust survivors are gone, that's all we're gonna have, is those conversations that we've had with them. So getting to see them experience these things are probably going to be my favorite part of teaching.

L: We registered with the National Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C., and this 90-year-old survivor saw our story. She called up her friends Peter and Dagmar Schroeder, and she said, ‘You're going to tennessee’ - they were German journalists stationed in Washington - ‘and you're going to write about these kids, so that they get their paper clips.’ And they did write, and they had their friend from the Washington Post come, Dita Smith, and she did write.

T: They came down, fell in love with the kids. I remember when they came, it was like having another set of grandparents walk in. They loved the kids.

Reflecting on the achievements of the project, and how it can inspire other rural schools, Linda and Taylor closed with the following advice for those wanting to pursue a career in rural education.

T: The thing I always tell my visitors, I had a professor, and she told me that my kids were too young to understand, that they did not know and they would not know what I was teaching them. We've had people come in that are teachers and ask, ‘What would you tell your kids?’ or ‘What should I tell my kids?’ And it’s never, ever underestimate what a child can understand. They will always surprise you, they will always understand more than you give them credit for, and if you just allow them to, they might actually teach you something.

L: I have been a teacher, I have been a principal, if there's anything in education I've probably had a hand in it at some point. To me the most, very most, important message that we have is: everything you do in life is a choice, and your choices are extremely important, and that it doesn't matter how old or how young or how rich or how poor or what color you are, you need to be committed to making the world a better place. Just look at the changes that have come about in the world because one person stood up for good or for evil.

T: I am Taylor Kilgore, and I am a rural teacher.

L: My name is Linda M. Hooper, and I am a rural teaching volunteer.

Thank you for engaging with this episode of the I Am A Rural Teacher Podcast. We’d like to thank our partners at the National Rural Education Association for collaborating with us on this episode. Special thanks to Linda and Taylor for welcoming the RSC team into their school and showing us the artifacts library. The I Am a Rural Teacher project is made possible by a grant from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

*Rural Schools Collaborative seeks to provide truthful accounts of the lives of educators in rural places, and at times that means recognizing the hard realities they face along with the good work they do. Sharing stories of struggle and hardship underscores the imperative need to support our educators and schools as well as highlighting how they nevertheless are persisting to innovate and provide invaluable services to our children and communities. This is the bedrock of our mission to seek sustainable community development through a keen focus on educators, place, and philanthropy.